When you read Stalin’s Wine Cellar – the wine book of the year for all kinds of reasons – there are definitely more questions raised than answered.

A couple of pages in, and you are asking yourself: ‘Is this a scam?’

Further into the book and you start Googling names (don’t bother, many have been changed) and trying to check the facts as they are presented by Sydney wine merchant, John Baker, as he explains how, in 1998, he was approached by a business acquaintance with a list that purported to be an inventory of a wine cellar once owned by Stalin and containing wines of the last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II.

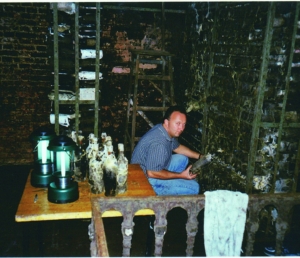

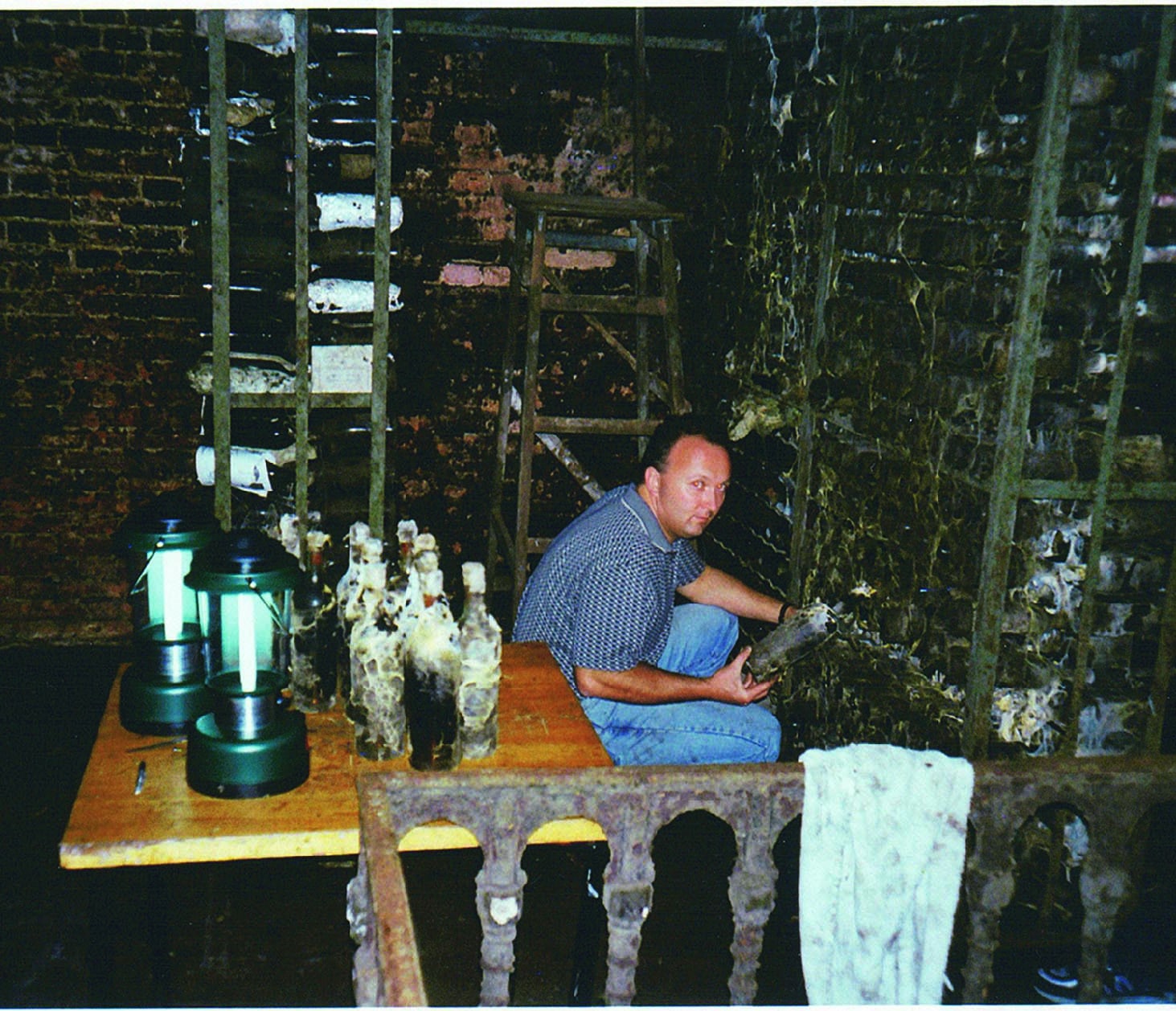

The alleged cellar was in the bowels of a Georgian winery. Stalin was born in Georgia and is said to have moved his cellar there when the Germans were close to invading Russia in World War II. The winery was in sad decay and the owners needed money to get it up and running again, and were willing to sell the wines.

So, Baker encouraged by his business acquaintance who wanted to put up money to check the story out (and benefit from the sale of the wines), was off to Georgia and one heck of a rollicking story now outlined in his book called Stalin’s Wine Cellar (Penguin, $35). It goes on sale today.

John Baker, then the owner of Double Bay Cellars, accepts that the story might seem hard to believe.

In the book, he and his store manager travel to Georgia and meet with a bunch of hard men guarded by heavy-drinking, gun-carrying cronies who give them the runaround, but eventually the two men get to see the wines. Or, rather they work off an inventory because most of the bottles no longer have labels.

He details an Aladdin’s Cave of truly astounding vinous wonders: Chateau Mouton Rothschild 1874, Lafite 1877, Margaux 1884, Suduiraut 1899, bottle after bottle of the world’s greatest dessert wine, Chateau d’Yquem from the 19th and 20th Century going back to 1847 and more.

Were they for real?

“When I realised what it was, this was the ultimate cellar,” he says.

“You just don’t get this sort of opportunity. If you look at the wines that were in there – I mean 217 bottles of d’Yquem from the 1800s and early 1900s, it just doesn’t exist.

“That’s 18 cases. It’s absurd. But it was there, we touched it and brought some bottles home.

“If wine people had the opportunity to just look at this, they would give their eye teeth for it wouldn’t they?”

They persuade the winery owners that the wines, many without labels due to the high humidity and dank cellar, need to be substantiated before the sale can continue and the duo leave the country with a small cache of wines, including a bottle believed to be d’Yquem with a cork, legible though the glass, reading 187- (the last digit missing). At the winery, the winemaker agrees that it tastes like an old d’Yquem.

Satisfied, Baker continues along his journey to secure the wines for auction in the West and that’s when things go terribly wrong.

John Baker is well-known in Sydney wine circles. His astounding story has been 22 years in the making and with real wine personalities involved in its telling, including the winemaker and president of Chataeau d’Yquem, some of it rings true.

But there are lingering questions, actually quite a few.

Like, when a story is too good to be true . . . and this is a very good story.